Ice Ages in Oxfordshire

BEHIND-THE-SCENES

Discover specimens that are not currently on display

The Pleistocene Epoch, more commonly referred to as the Ice Age, lasted from 2,600,000 to 11,700 years ago. During the Pleistocene, cycling global temperatures resulted in an alternating sequence of cold 'glacial' periods, when glaciers expanded, and warmer 'interglacial' periods, when they receded. The Oxfordshire landscape is rich in Pleistocene fossils, thanks in a large part to the River Thames and its tributaries. Flowing across the county for over half a million years, the Thames has deposited sediments, trapping and burying plant and animal remains that have sometimes fossilised. By studying these fossils, we can reconstruct the Oxfordshire of the past, and learn more about how animal and plant species were able to respond to the Pleistocene's changing climate.

INTERGLACIAL FOSSILS

GLACIAL FOSSILS

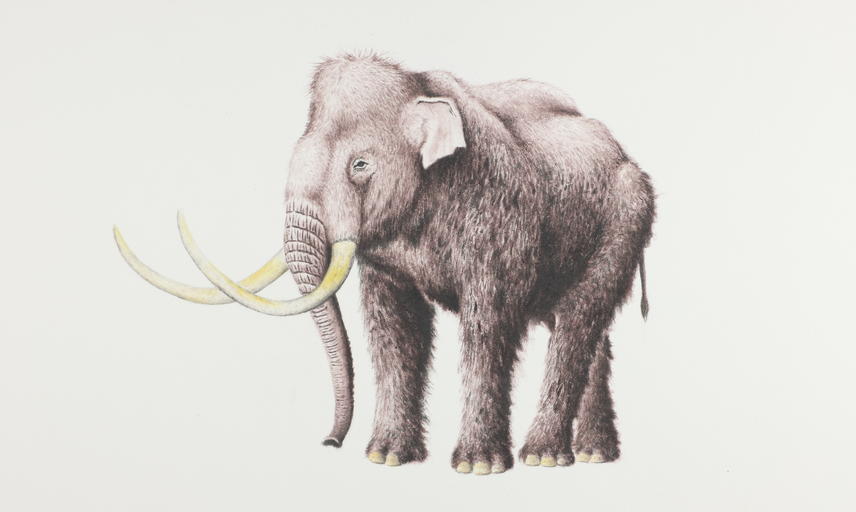

ELEPHANTS AND MAMMOTHS

LOCAL FOSSIL SITES

INTERGLACIAL FOSSILS

In addition to fossils dating from the icy, glacial periods of the Pleistocene, there are also a variety of interglacial fossils in the Museum's collections. By comparing interglacial fossils to glacial fossils, we can gain valuable insights into how life on Earth has responded to past periods of environmental change, and project how today's wildlife will respond to future warming caused by human-induced climate change.

Six miles west of Oxford, the village of Stanton Harcourt resides next to a fossil site rich in interglacial material from a warm spell that took place 200,000 years ago. Detailed excavations of ancient river sediments in the 1990s revealed over 1500 fossils belonging to large mammals, like elephants, mammals, bison, lions and bears. Even more exceptionally, thousands of remains of plants, insects and molluscs have been uncovered, allowing us to reconstruct this ancient environment to an unparalleled degree. There are even traces of early humans to be found at the site, with stone tools excavated from layers dating to 200,000 years ago. These tools would have been made by Homo neanderthalensis, or Neanderthals, which began to inhabit Britain as far back as 400,000 years ago.

What Oxfordshire might have looked like during interglacial periods of the Pleistocene

https://www.thinglink.com/card/1651559356392538113

© Neil Owen and Oxford University Museum of Natural History

As well as the remains of large animals, an extraordinary variety of plants were preserved at Stanton Harcourt. This included trees, shrubs, flowers, grasses, and aquatic species. A variety of tissues from these species were preserved – such as leaves, seeds, nuts, spores and pollen – though fossilised wood was especially abundant, with twigs, branches, logs, and even entire root systems present at the site.

The plant species identified at Stanton Harcourt indicate that the fossils date from a warm, fully interglacial period during the Pleistocene era. In particular, preserved material from mature deciduous trees, such as oak, beech, hornbeam and hazel, indicate that climates were warm and stable for an extended period of time. The seeds and spores that were excavated are typical of vegetation found next to a slow-moving river. Overall, it seems that, 200,000 years ago, Stanton Harcourt was a lightly wooded environment with open areas of dry and wet grassland.

At least six species of caddisfly and over 115 species of beetle were found in the river sediments at Stanton Harcourt. Fossilised insects are valuable finds because they provide detailed information about the environment and climate at the time they were alive.

All of the species identified at Stanton Harcourt are still around today, meaning we can use information about the habitats they currently live in to determine what the climate might have been like in Oxfordshire 200,000 years ago. Overall, it seems that the average temperatures in July would have been 17oC to 18oC, and -2oC to 2oC in January — about the same, or a little warmer, than the climate today.

54 species of molluscs, including freshwater clams, mussels, limpets and snails, were found at Stanton Harcourt. These included whole layers of clam and mussel shells, sitting in 'life position', i.e. laid out as they would have been when living in the river.

Freshwater mussels excavated from Stanton Harcourt.

Photo by Kate Scott.

GLACIAL FOSSILS

What Oxfordshire might have looked like during glacial periods of the Pleistocene

A number of Oxfordshire's fossil sites date to the colder, glacial periods of the Pleistocene. During these freezing spells, much of Britain's landmass would have been inhospitable to wildlife, covered in kilometre-thick ice sheets.

The most recent of the glacial periods in Britain is known as the Devensian. During the Middle Devensian, the climate warmed slightly, allowing grasslands to spread over the UK. Despite the bitter cold, these vast, grassy plains were able to support huge herds of grazing mammals. This would have included woolly mammoths, woolly rhinos, steppe bison, horse, and reindeer, accompanied by carnivores like spotted hyaenas, wolves, lions, and brown bears. So far, we have uncovered over 1000 fossils of large mammals in Oxfordshire that date to Middle Devensian (30,000 – 60,000 years ago), a number of which have been found in gravel pits like those at Sutton Courtenay. As well as finding direct evidence of species through fossilised bones, the characteristic gnaw-marks of hyaena teeth on woolly rhino and bison bones tell us who would have been eating who! Findings of stone tools from this era prove that humans were active in the landscape too. These tools were probably made by some of the last Neanderthal populations in Europe, just before our own species, Homo sapiens, first arrived in Britain ~40,000 years ago.

https://www.thinglink.com/card/1651578291087212545

© Neil Owen and Oxford University Museum of Natural History

LOCAL FOSSIL SITES

Oxford University Museum of Natural History is home to many fossils from the Pleistocene, including those that have been collected from local sites. A few of these sites are marked below...

https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/1/embed?mid=1qDCIxTt1s91LI2W-zrX_NeP7-Ad0sn8T&ehbc=2E312F

Browse Collections Online

and view specimens from these fossil sites...

Pleistocene

Pleistocene

Pleistocene

FIND OUT MORE

Acknowledgements:

Neil Adams (content) – Hilary Ketchum (content) – Neil Owen (illustrations)

With thanks to the Street Foundation.

We acknowledge the assistance of the Curry Fund of the Geologists' Association.