Olli's Blog

Olli Ellis was a part of the museum's Undergraduate Bursary Scheme 2025 on the project 'Engaging Families and Young People with Science and Nature.'

Recruitment for 2026 Scheme is now open. You can apply here

Having gone straight from GCSEs to college to university, most of my life has been entrenched in the rigid structure of formal education, which has made me all too aware of its pitfalls and struggles. Formal education is a necessary and important aspect of learning for a lot of people, but for just as many it is a barrier to science and our natural world, built on jargon and required reading.

During my 5-week placement within the public engagement team, I’ve learnt a lot about how to capture audiences’ instinctual fascination with the natural world and encourage learning through interactive and self-guided activities. It also taught me a lot about myself, and my own unique way of teaching and connecting to audiences – something that my dissertations and scientific papers had never taught me at uni.

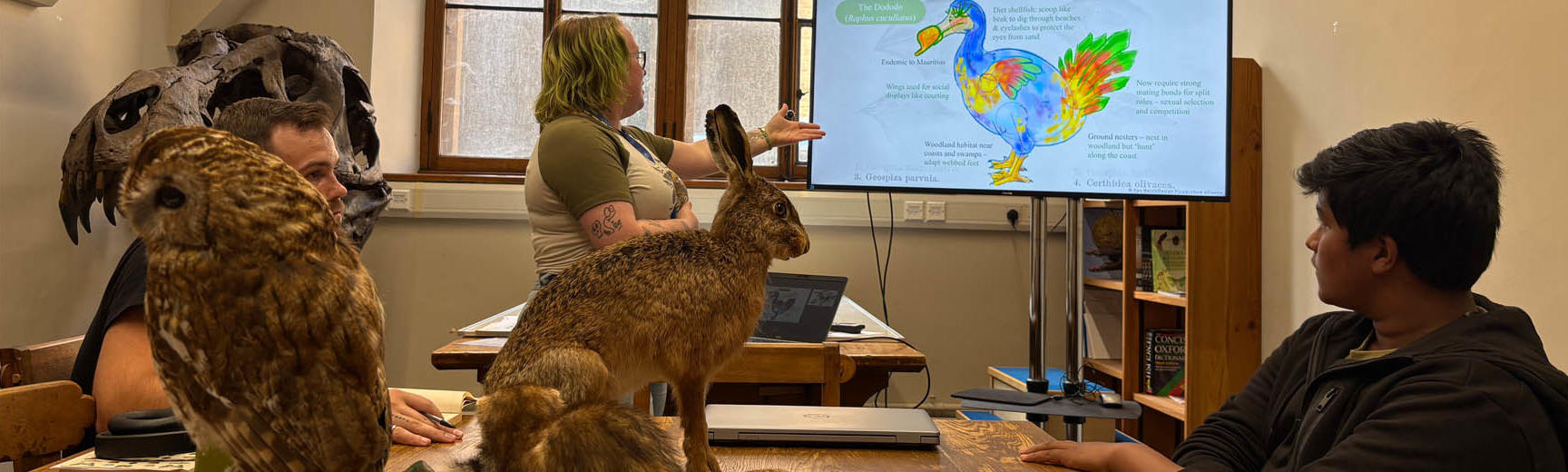

Through the support of the team, I was able to develop and run my own activity to two separate audiences. The activity was specifically tailored to two of my interests: evolution (an interest my university education has strongly encouraged), and artistic expression (less encouraged by the dissections and reports of formal scientific education).

After a short lecture and discussion on what evolution is, how natural selection works, and how animals adapt to their environment, I introduced another fascination of mine – speculative evolution; hypothetical life. We had a small array of taxidermy from the museum’s handling collection, which I asked the groups to use as inspiration to imagine and illustrate how a species might evolve and adapt over a million years.

It was incredible how quickly pens and pencils began to fly across paper, and how excited participants were to create their own wild and wacky version of an owl or rat or mole. I had given them only one pejorative: be able to explain and justify the changes made to your species. They did not disappoint.

It was not until I began to see the creative vision of rats that can produce electrical fields or crocodiles reimagined as draconian beasts that I realized just how constrained my own examples had been, being a dodo evolving into a more tropical bird and a koala developing pink fur and toxic venom. For both groups, the creativity poured onto the page and along with it, the understanding of evolution.

It is all well and good to understand how evolution has impacted animals in the past; how creatures went from water to land (and some back to water), how fur and feathers and scales have come to exist, but it is another thing entirely to try and project what will change in the future. When you imagine a great change, such as a koala with toxic venom, and have to justify and consider why that might come to evolve, the process of evolution becomes much clearer: koala’s eat eucalyptus leaves, which are largely toxic to most other animals, over time mutations may allow the koala to retain the toxic chemicals, storing them in saliva to help defend against predators or competitors in the drastically reducing habitat of Australian woodland.

This activity was one of few run during my placement, but it stands out to me above all else. It is through this activity that I developed my confidence in presenting and communication science effectively, and that I began to understand how to implement informal learning to help make natural sciences much more accessible, and fun!